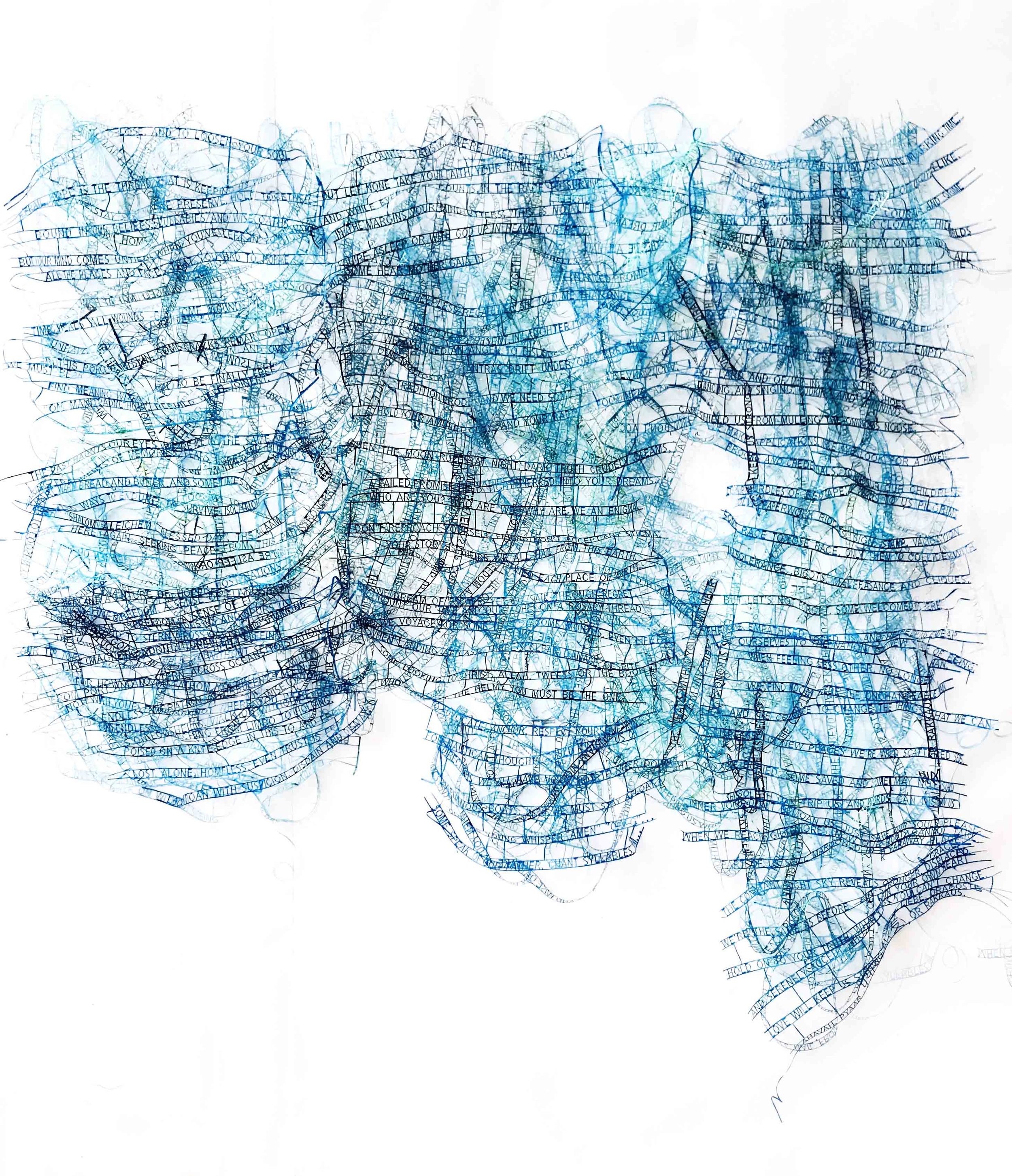

Poetry Net (I), shortlisted for the Sovereign Asian Art Prize 2020

[Press release here]

1. How do you feel about being shortlisted as a finalist in the Sovereign Asian Art Prize 2020?

I was honoured to be selected as a finalist to represent Singapore, finding out early in 2020 and being officially announced on Wednesday (18th March). I make work about the stories of others, so I am also pleased on behalf of the communities I work with, that this can help share their stories and build compassion between diverse peoples.

2. What is the artwork about?

I have long been making artworks about migrants - those who are part of the modern crisis as well as those who had to migrate throughout history due to wars and genocides, disenfranchisement or displacement and, most recently, climate change displacement. In my research and interviews I noted repeatedly that even in the darkest times, communities and individuals expressed thoughts about hope, love and home. These concepts are vital to human existence, and helped them survive. They approached these through their own words or those of prayer, mantra, sayings, aphorisms, or simply words of advice they have held on to. These sentiments stood out to me as a way to manage the most challenging times of existence, and I wanted to make an artwork about that collective mantra of survival when life is overwhelming.

3. How is Poetry Net (I) made?

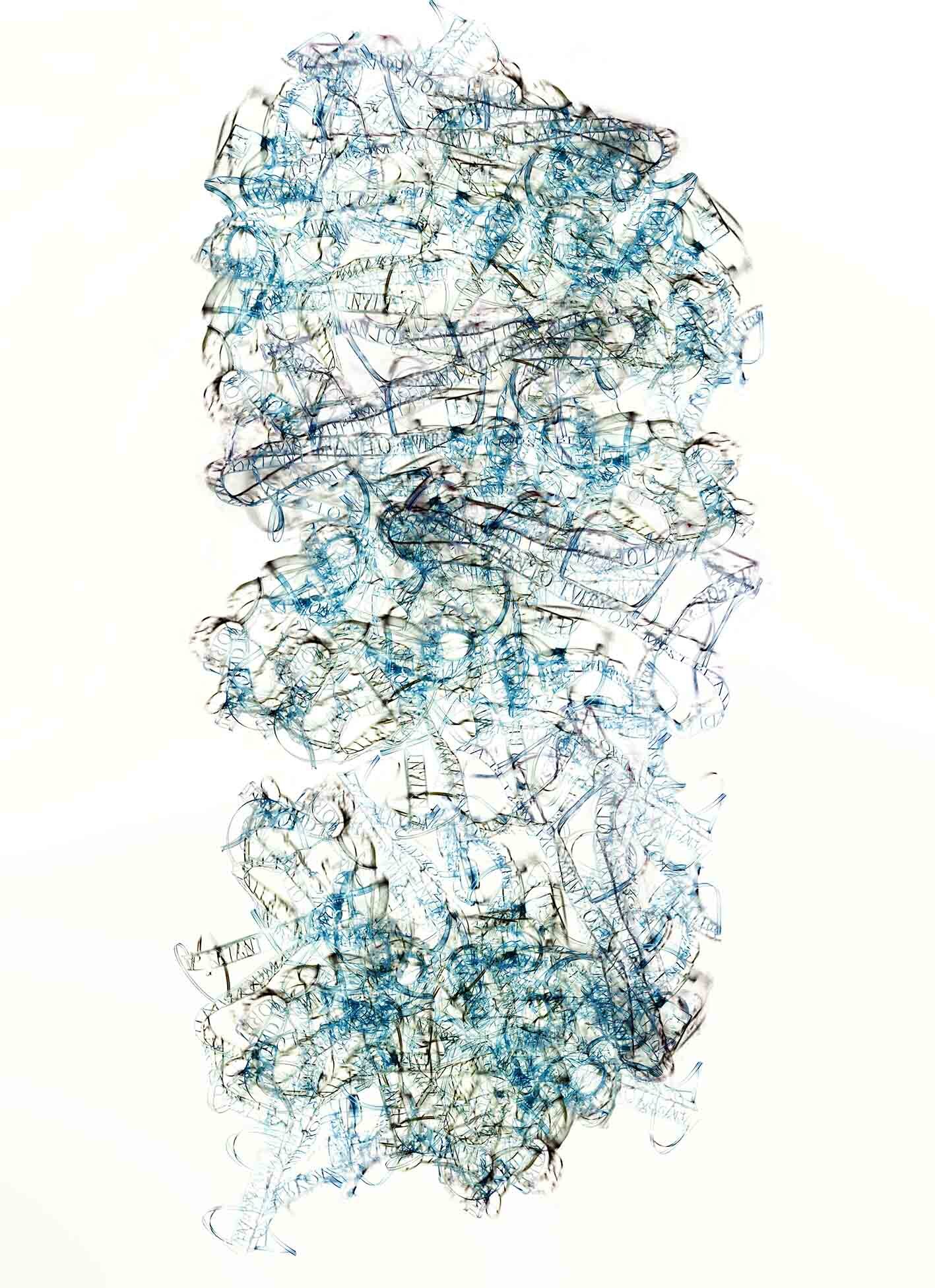

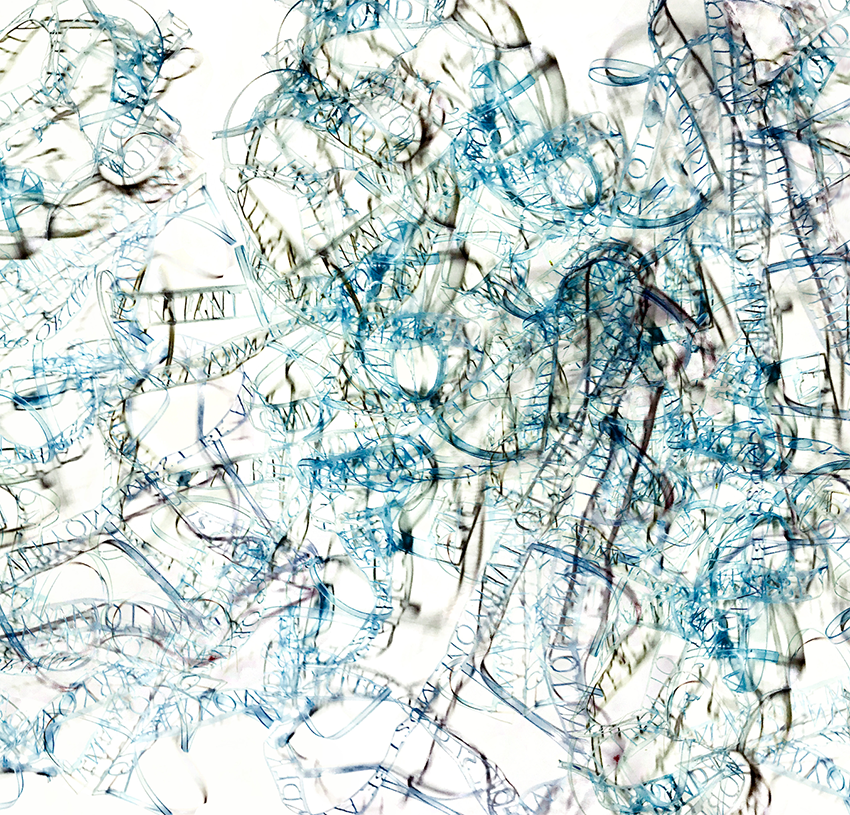

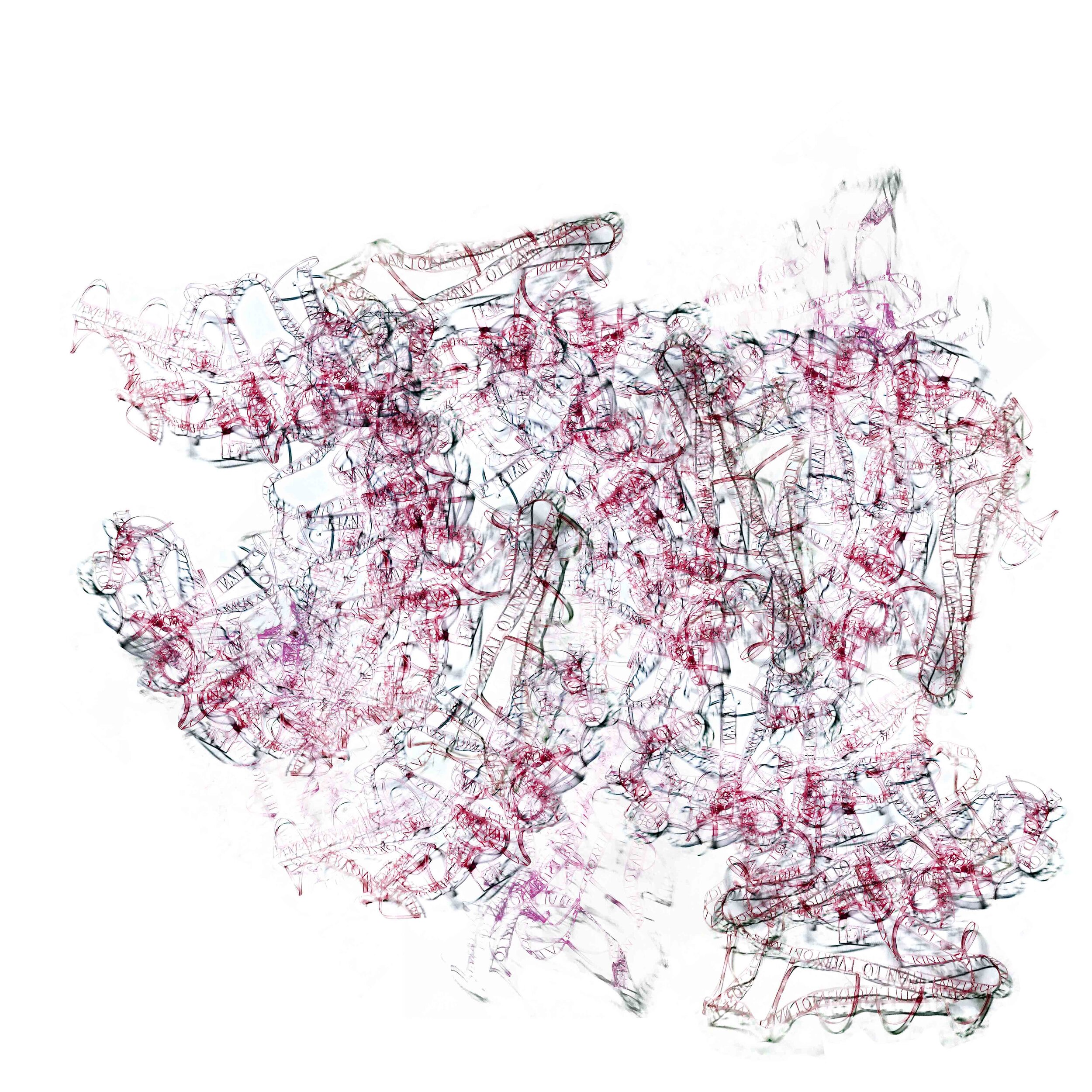

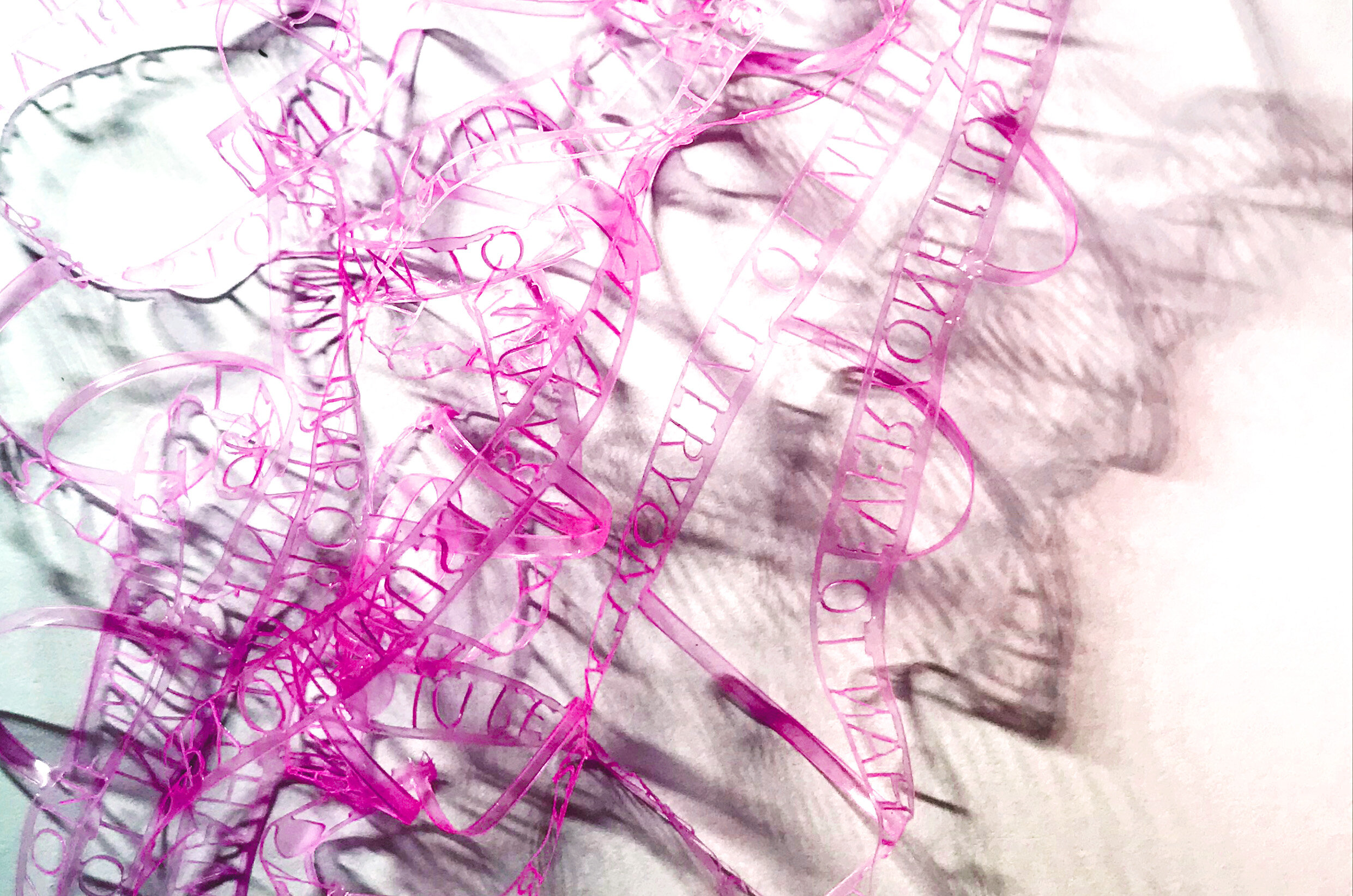

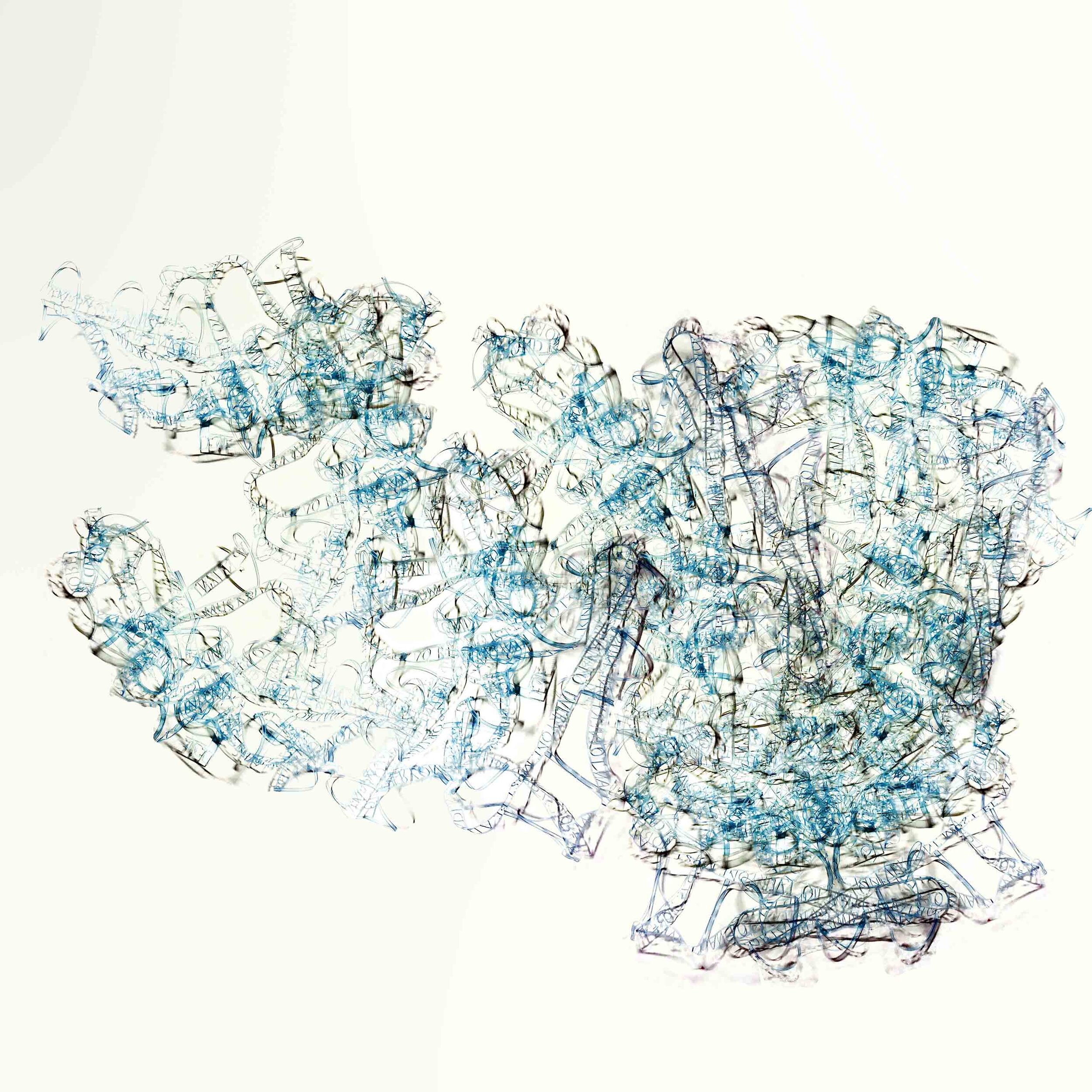

The Poetry Nets are 'text artworks' made using the protective plastic usually found on acrylic sheets. This film usually gets thrown away, but I liked the irony of something which is there to protect from harm - then being discarded without thought. I asked - why not use it? I am seeking ways to be more sustainable, and to encourage others to think about finding beauty in reusing, recycling, and saving - not discarding.

So, I cut these translucent films by hand and by machine, turning them into lace-like structures of text, which reminded me of nylon fishing nets. I used to live on Beach Road, being inspired by the fishing supply shops, and have always been keen to use fishing nets in my artwork. Instead of the usual grid-like fishing net, the net's shape is letters - cut, knotted and tied into a web of text.

4. How long did it take?

These pieces have taken over five years to compose because the research process involved collecting stories and testimonies via interviews conducted across Asia and Europe, gathering individual testimonies and collective memory. I focus on those who are displaced, noting what migrant communities express about hope, love, and what keeps them going.

Locally I worked with H.O.M.E. charity and Yellow Ribbon Project. Internationally I worked with UNHCR, Ireland's Centre for creative practices, & The Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles who enabled me to source testimonies of Holocaust and Rohingya genocide survivors. I also worked with communities of migrants and refugees around the world.

5. Tell us about the poem that the artwork contains.

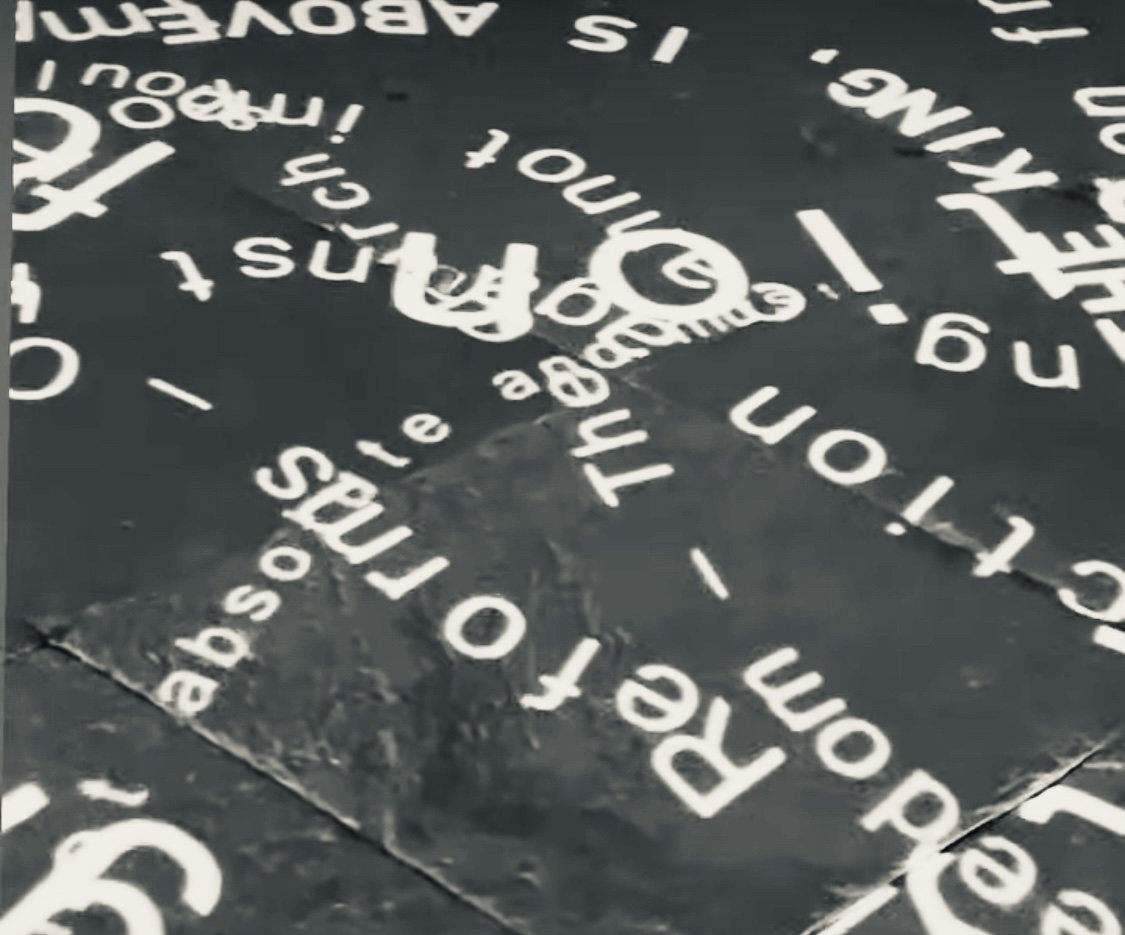

I wrote a poem called 'The thread that binds us' - not many people know that I also write as well as make sculpture, because I usually feature someone else's life story in my work, or collaborate with a poet. (The full poem can be found here)

In this case, I wanted to represent the sentiments of hundreds of people, about how they deal with being without a home, shifting identities, endangerment and battling with a sense of 'otherness'. The poem takes fragments of prayers, mantras, sayings, aphorisms, kind words - These sentiments stood out as a shared human mantra.

The text is available to the public either in a book to be published later this year, or on my blog here.

Below is an excerpt:

'Dispersed in new places we’re wild scattered seeds:

some buried, some saved and some may not succeed

Shibboleth can trip us, and words can disown us

Inner voice don’t bemoan us: just save our souls please.

When we reach gilted shores, now our roots cannot take,

part of us still marooned in a faraway place.Time heals all wounds - but some wounds become us

Unravel your self, find a jewel in the lotus

In this porcelain skin, some cracks remain open,

we must bear them, become them, love them and own them

Find meaning within them, to be finally free,

“Om mani padme hum”, rebuild gold joinery.’

6. What does the piece mean to you personally?

The fishing net motif has recurred in my work as a symbol of the tension between capturing, saving, rescuing, or providing - with reference to the global migrant crisis which has left families stranded and drowning.

I am most interested in the human-ness of stories, and the archive of these stories that exists within each individual, each family, each generation - something I am often aware of in Singapore when looking at the rich memories and traditions, but also the sense of loss and nostalgia.

Personally this subject area is close to my heart because my family migrated from Asia to Europe before I was born, every day I am thankful for the difficult journeys they made to provide a better, safer life for their children and grandchildren.

7. What was most challenging?

By far the most challenging thing was representing over 100 voices in one poem and one artwork, finding the thread that binds and connects them together, whilst staying true to those individual people's statements and words. The writing took a long time and I had to balance accurately quoting people with literary style and poetic devices. A lot of my work has that ethical requirement to be true to the text.

8. Has Poetry Net (I) been showcased yet? Tell us about the series.

It is part of a series, and these pieces are a subsequent evolution of the text sculptures which featured in my solo exhibition at Singapore Art Museum in 2017, and in the Singapore Festival Yangon this year. However this particular series has not been shown publicly yet - I am looking forward to unveiling piece one for the Sovereign Art Prize exhibition in Hong Kong this May.

9. What is the artwork about?

I have long been making artworks about migrants - those who are part of the modern crisis as well as those who had to migrate throughout history due to wars and genocides, disenfranchisement or displacement and, most recently, climate change displacement. In my research and interviews I noted repeatedly that even in the darkest times, communities and individuals expressed thoughts about hope, love and home. These concepts are vital to human existence, and helped them survive. They approached these through their own words or those of prayer, mantra, sayings, aphorisms, or simply words of advice they have held on to. These sentiments stood out to me as a way to manage the most challenging times of existence, and I wanted to make an artwork about that collective mantra of survival when life is overwhelming.