PLAIN TEXT:

Myanmar, Notebook June 2020

In parallel

San Lin Tun

Lim Chin Tsong Palace, Yangon // San Lin Tun

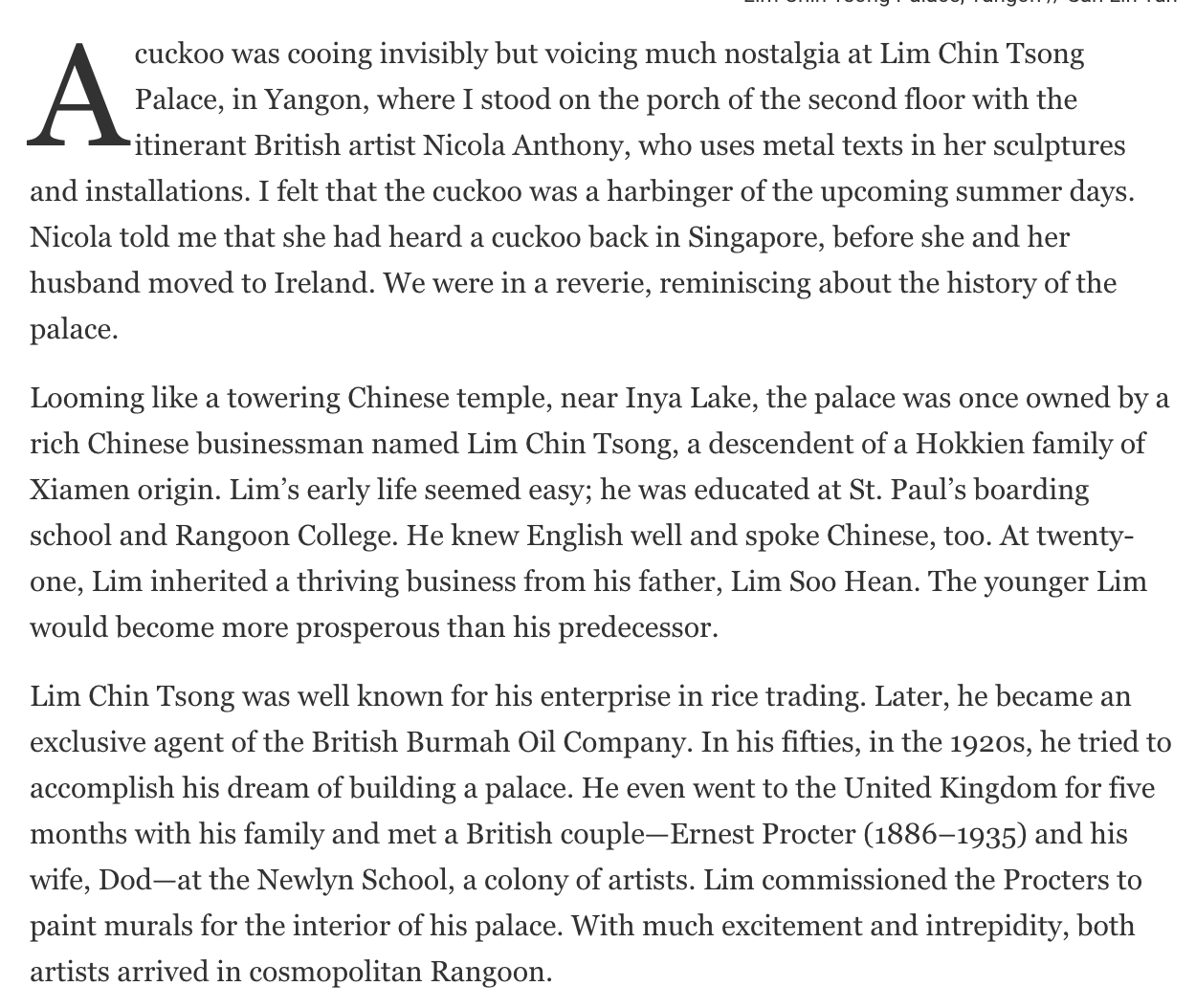

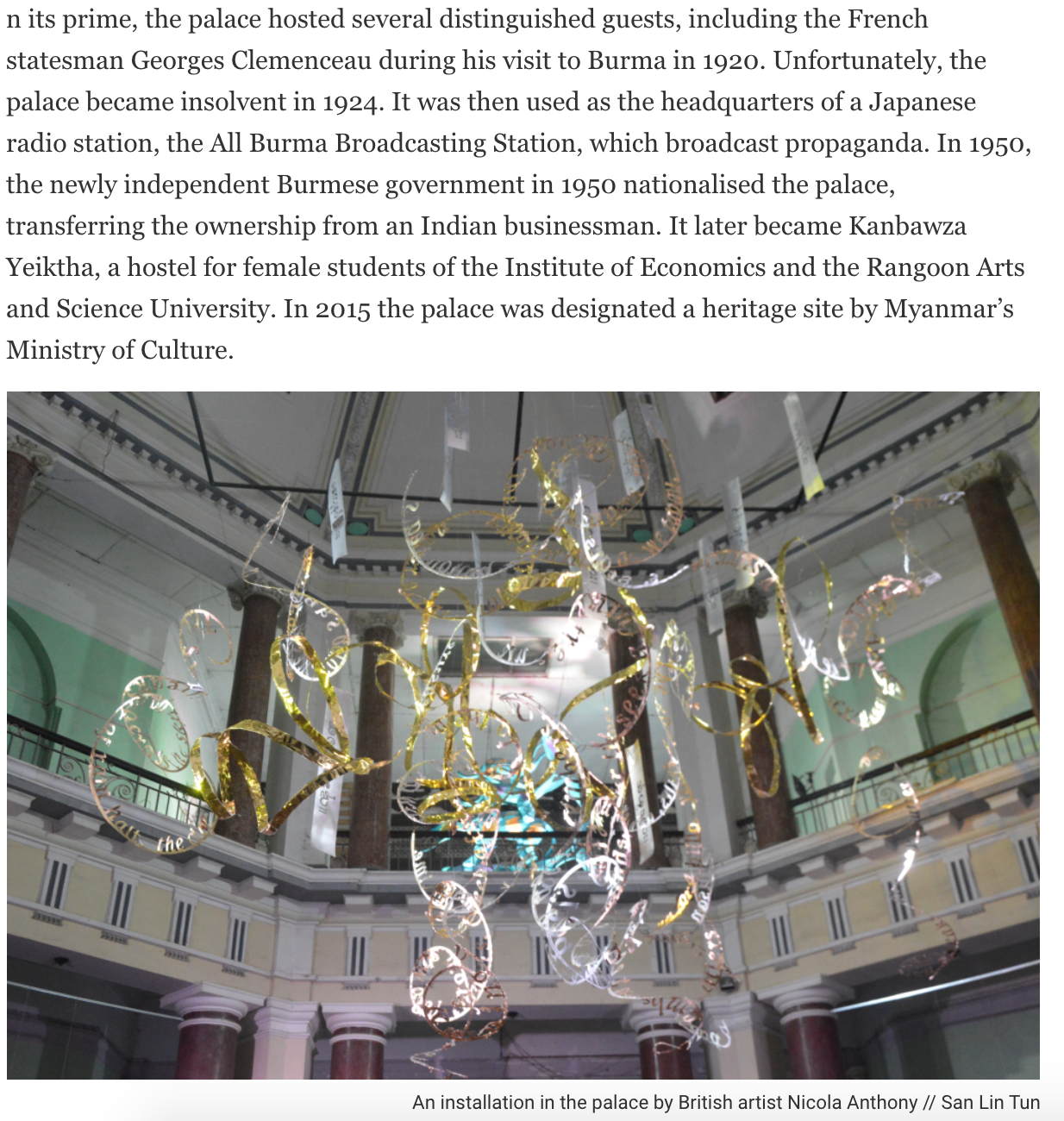

Acuckoo was cooing invisibly but voicing much nostalgia at Lim Chin Tsong Palace, in Yangon, where I stood on the porch of the second floor with the itinerant British artist Nicola Anthony, who uses metal texts in her sculptures and installations. I felt that the cuckoo was a harbinger of the upcoming summer days. Nicola told me that she had heard a cuckoo back in Singapore, before she and her husband moved to Ireland. We were in a reverie, reminiscing about the history of the palace.

Looming like a towering Chinese temple, near Inya Lake, the palace was once owned by a rich Chinese businessman named Lim Chin Tsong, a descendent of a Hokkien family of Xiamen origin. Lim’s early life seemed easy; he was educated at St. Paul’s boarding school and Rangoon College. He knew English well and spoke Chinese, too. At twenty-one, Lim inherited a thriving business from his father, Lim Soo Hean. The younger Lim would become more prosperous than his predecessor.

Lim Chin Tsong was well known for his enterprise in rice trading. Later, he became an exclusive agent of the British Burmah Oil Company. In his fifties, in the 1920s, he tried to accomplish his dream of building a palace. He even went to the United Kingdom for five months with his family and met a British couple—Ernest Procter (1886–1935) and his wife, Dod—at the Newlyn School, a colony of artists. Lim commissioned the Procters to paint murals for the interior of his palace. With much excitement and intrepidity, both artists arrived in cosmopolitan Rangoon.

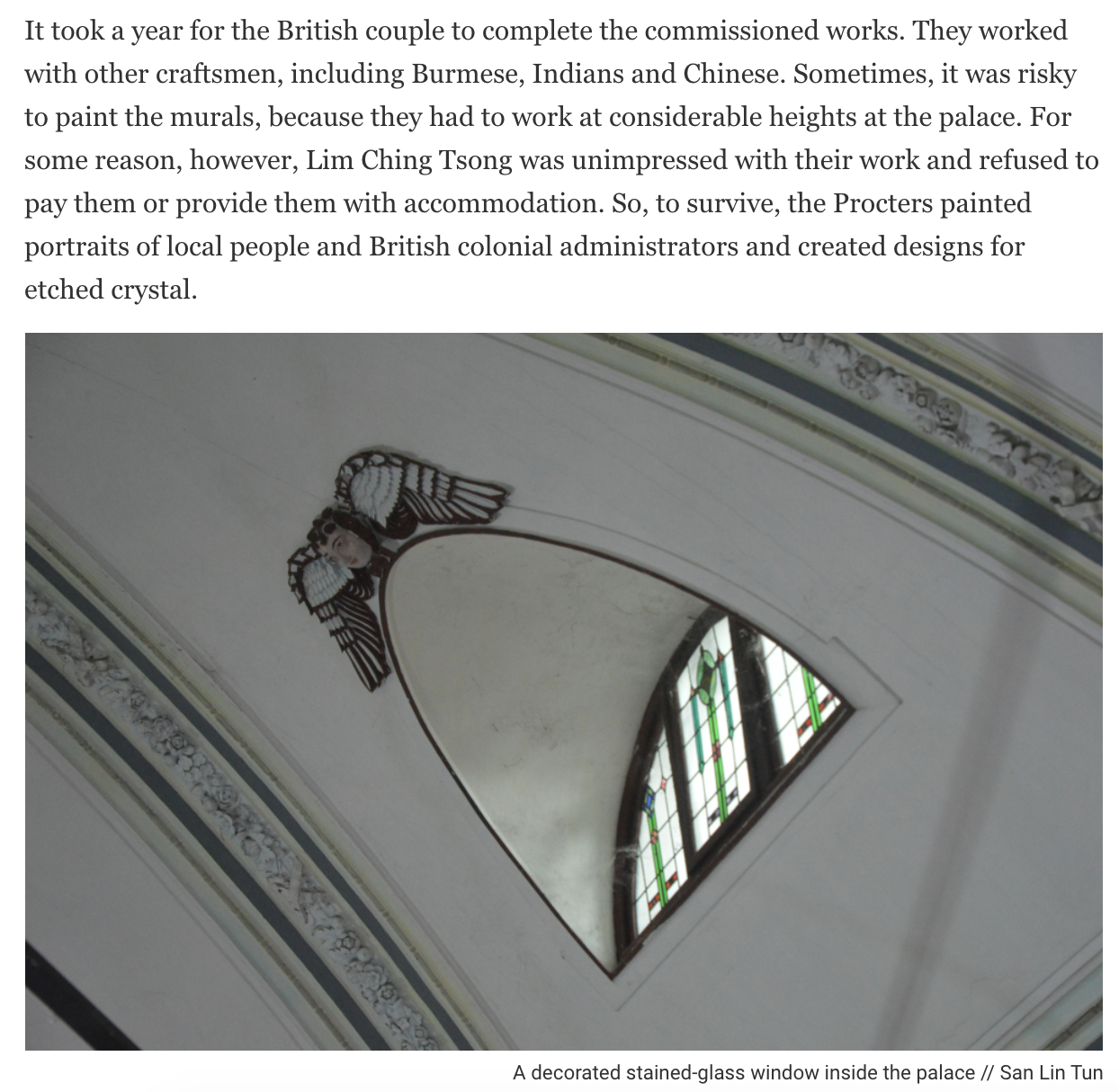

It took a year for the British couple to complete the commissioned works. They worked with other craftsmen, including Burmese, Indians and Chinese. Sometimes, it was risky to paint the murals, because they had to work at considerable heights at the palace. For some reason, however, Lim Ching Tsong was unimpressed with their work and refused to pay them or provide them with accommodation. So, to survive, the Procters painted portraits of local people and British colonial administrators and created designs for etched crystal.

Lim Chin Tsong was born in 1867, whereas Ernest Procter was born in 1886, a year after the annexation of Burma by the British Empire. They chose different paths: one was engaged in business; the other pursued art. But their chance encounter in the United Kingdom resulted in their painting spectacular murals at Lim Chin Tsong Palace.

Both men participated in the First World War. Lim was awarded the Order of the British Empire in 1919 for his fundraising efforts during the war, while Procter served with the British Red Cross as an orderly in Dunkirk. His war experiences are reflected in his art. Both men died unexpectedly, too: Lim, at his palace, in 1923 and Procter in 1935. For me, learning about Lim’s life is like reading The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Procter, a native of Tynemouth, Northumberland, was known as a fine landscape and portrait painter. He studied art at Stanhope Forbes’s School of Painting for three years (1907–1910). At the age of twenty-four, in 1910, he went to Paris and studied at Atelier Colarossi. He married fellow painter Dod Shaw in 1912 and they lived in France for a number of years. Then they returned to Newlyn, a seaside city in southwest England, where they would later meet Lim.

Though the Lim Chin Tsong Palace stands prominently in Yangon, not many people know much about it or its murals. Some speculate that its original owner must have been very rich and wonder how and why he built this beautiful building in Yangon. They know that it used to house the state’s fine-arts school after it moved from the old A.F.P.F.L building (now the Goethe Institute Yangon) at the Yey-Khel-Sine bus stop.

Apart from the murals at the palace, Procter painted, in oil, rural scenes such as ‘On the Banks of the Irawaddy’ (1912) and ‘Burmese Boy in a Bullock Cart’ (1925); the latter was included in the private collection of the head of the British Burmah Oil company, Cecil Maxwell-Lefroy. Later in life, Maxwell-Lefroy donated his collection to the British Museum.

Though the original owner of the palace and the creator of the mural paintings are gone, the mural paintings are still intact, exhibiting their unquenchable beauty to people and serving as heritage pieces. The murals are the distinctive links between Lim Chin Tsong and Ernest Procter, whose lives crossed at one point while they were pursuing different goals. They might not have expected that their collaboration would create invaluable aesthetic value for future generations.

n its prime, the palace hosted several distinguished guests, including the French statesman Georges Clemenceau during his visit to Burma in 1920. Unfortunately, the palace became insolvent in 1924. It was then used as the headquarters of a Japanese radio station, the All Burma Broadcasting Station, which broadcast propaganda. In 1950, the newly independent Burmese government in 1950 nationalised the palace, transferring the ownership from an Indian businessman. It later became Kanbawza Yeiktha, a hostel for female students of the Institute of Economics and the Rangoon Arts and Science University. In 2015 the palace was designated a heritage site by Myanmar’s Ministry of Culture.

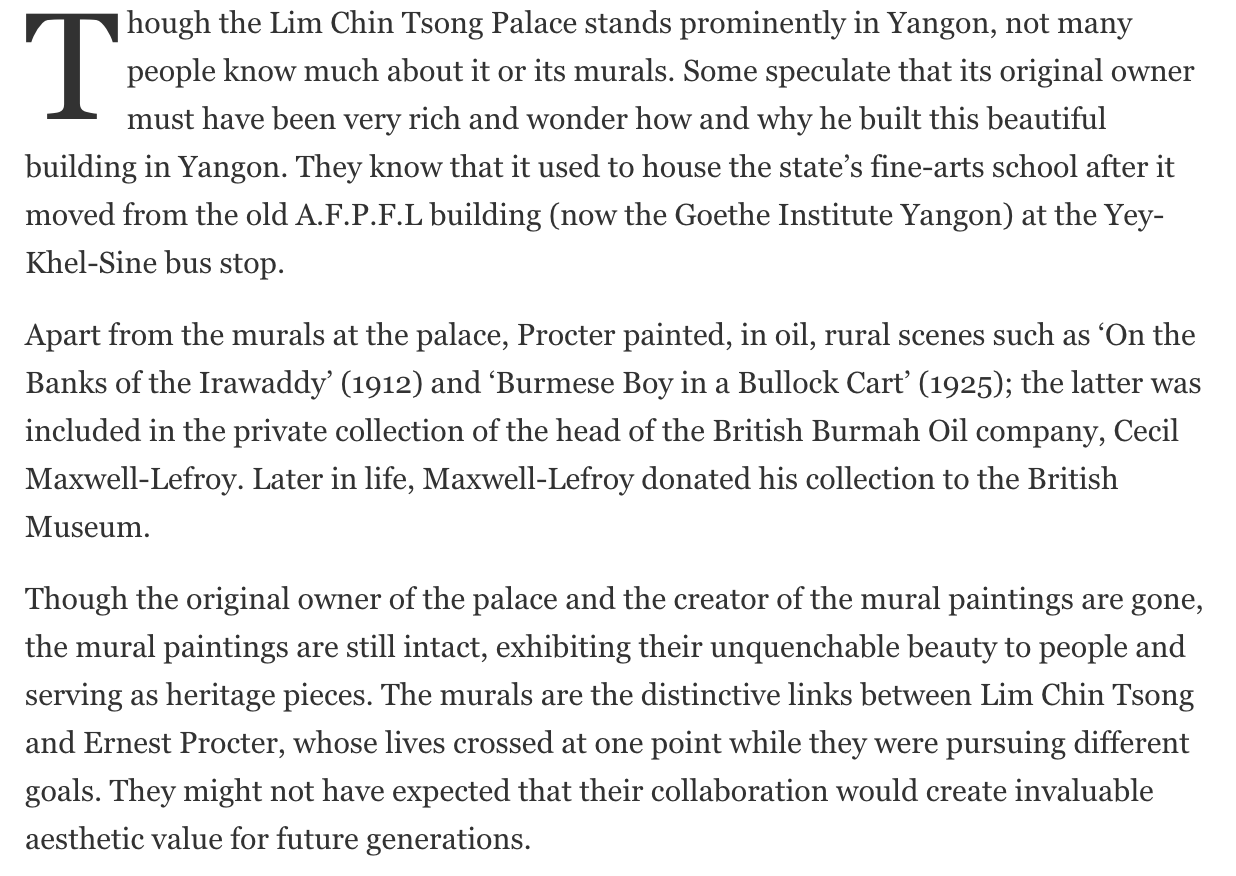

An installation in the palace by British artist Nicola Anthony // San Lin Tun

The evening sun set in behind our backs. Down below, we could see some of the Singapore Festival’s activities on the front lawn of the palace. We talked casually about art and the art scenes of Yangon, Singapore and the United Kingdom until we returned to the exhibition floor, where the curator Marie-Pierre Mol of Intersections Gallery in Singapore had arranged the theme: ‘Art Walk: Time is Yours’, with collaborations between Myanmar- and Singapore-based (and related) artists, including Marc Nair, Pang, Maung Day, Bart Was Not Here and Nann Nann.

The contemporary and conceptual art on display contrasted with the palace’s relics, interior decorations and murals. The fusion of old and new heralded a message about how time seemed to fly unnoticeably in this building. Time had washed away the newness of the palace but seemed to have increased its solemnity and aesthetic value. Suddenly, I remembered a line from one of Nicola’s installations: ‘Namhsan tea leaves perfume our minds …’ Likewise, I hope that the murals of the palace charm our hearts ad infinitum.

San Lin Tun is the author of the novel An English Writer. He lives in Yangon.