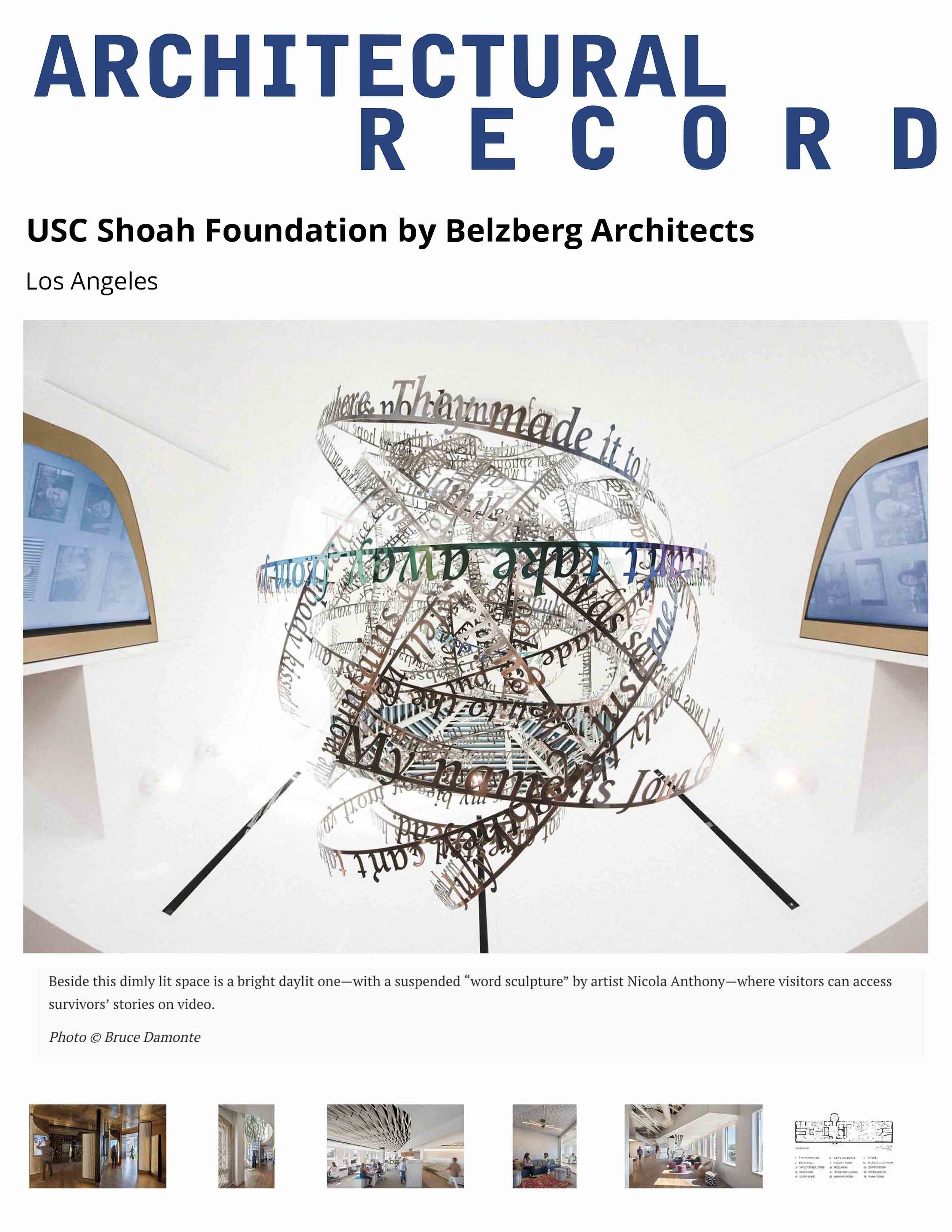

I am pleased to report that my piece ‘Remembering Our Father’s Words’ was featured in Architecture Record. The article discusses the unveiling of The USC Shoah Foundation’s permanent exhibit which presents the testimony of holocaust survivors.

Read the full article below or here

USC SHOAH FOUNDATION BY BELZBERG ARCHITECTS | LOS ANGELES

BY SARAH AMELAR | ARCHITECTURAL RECORD | March 7th 2019

‘ Twenty-five years ago, when Steven Spielberg finished directing the movie Schindler’s List, he realized his work was not done. Many Holocaust survivors’ stories still needed to be told—to preserve their memories, to bear witness, to learn from the past. He soon established the Shoah Foundation, dedicated to capturing such personal narratives on video. The organization has since archived more than 54,000 recordings in 43 languages and expanded its mission to seek out testimonies from genocides in Rwanda, Cambodia, Guatemala, Armenia, and elsewhere. Educational organizations worldwide subscribe to the archive. But the institute had no publicly accessible headquarters until last November, when Santa Monica, California–based Belzberg Architects (BA) converted the top floor of a University of Southern California (USC) library into the foundation’s 10,000-square-foot “mother ship.”

Now called the USC Shoah Foundation (USCSF), the institute began, in 1994, in trailers at Universal Studios, joining USC in 2006 and moving to cubicles on campus. Lacking was accommodation for visitors, teamwork, or programs that could include distinguished speakers, outreach to school children, and scholarly research residencies. The staff needed an open, collaborative environment with flexibility, and respite from the emotionally intense work.

BA principal Hagy Belzberg, knowing his own family’s Holocaust history, understood the importance of a safe-feeling, comfortable setting, particularly for survivors who might visit, work here, or come to record testimony. Now the elevator doors open directly into a soothing atmosphere, distinct from the existing library beneath. The lighting is subdued, sobering, filtered overhead through amber metal mesh. A forest of pillars—digital kiosks—invites individuals to explore USCSF’s offerings, as live lectures, or other content, animate a large, interactive back wall. While immersive, the space also connects with views outdoors, a conscious measure, across the entire floor, to keep it from ever seeming confining.

Bordering this entry hall is a daylit zone, with a suspended word-sculpture integrating phrases from one survivor’s testimony. With glass doors leading into other spaces, this area has a welcoming, luminous transparency, but unauthorized visitors can go no farther. “Given the subject matter’s sensitivity,” says Belzberg, “it needed high security without losing the feeling of openness. It’s a subtle balance.”

The west wing includes meeting and research areas, plus places the public can experience by invitation or tour. One room offers a survivorled, virtual-reality walk through a concentration camp while, in a lounge, visitors can converse, via artificial intelligence, with a videoed Holocaust survivor, who appears life-size, onscreen.

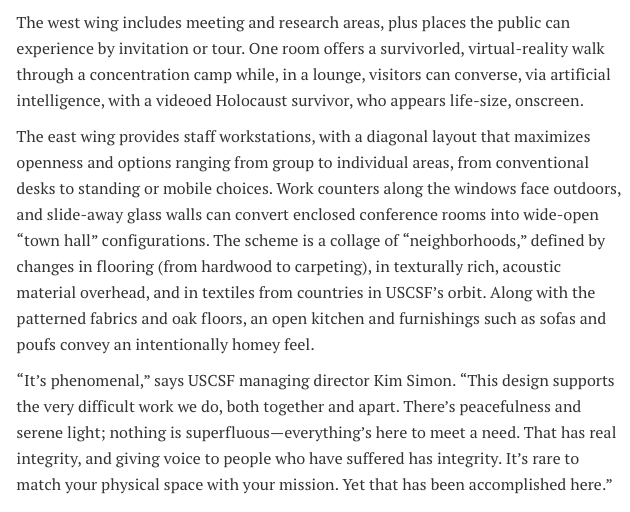

The east wing provides staff workstations, with a diagonal layout that maximizes openness and options ranging from group to individual areas, from conventional desks to standing or mobile choices. Work counters along the windows face outdoors, and slide-away glass walls can convert enclosed conference rooms into wide-open “town hall” configurations. The scheme is a collage of “neighborhoods,” defined by changes in flooring (from hardwood to carpeting), in texturally rich, acoustic material overhead, and in textiles from countries in USCSF’s orbit. Along with the patterned fabrics and oak floors, an open kitchen and furnishings such as sofas and poufs convey an intentionally homey feel.

“It’s phenomenal,” says USCSF managing director Kim Simon. “This design supports the very difficult work we do, both together and apart. There’s peacefulness and serene light; nothing is superfluous—everything’s here to meet a need. That has real integrity, and giving voice to people who have suffered has integrity. It’s rare to match your physical space with your mission. Yet that has been accomplished here.” ‘